Or just dumber at how we measure brain health?

There have been several articles lately describing the demise of contemporary brain health relative to how “smart” we were 100-150 years ago. Could our brains be decreasing in functional capacity? Has intelligence gone down over the past several decades? We’ll avoid any politically motivated discussions and think about whether there is any data that supports this. We won’t discuss whether there is a degenerative process ongoing in the school systems, but rather focus on the data that has been collected over the past 150 years.

Some of the assertions about modern day brain function originate from comparisons of studies conducted in the 1860s-1880s with contemporary studies. Reaction time is a metric that should be particularly telling, as it has been measured routinely over the past 150 years (first publication that we have run across is frmo the 1860s). It is a relatively simple task – deliver a stimulus to a subject (e.g. a tap to the skin, a flash of light to the eyes, or a sound to the ears) and the subject responds as fast as he or she can. From the 1860s through the 1880s, the response devices used to measure reaction time were commonly chronograph or pendulum based, and had resolutions of about 10 msec. In the 1880s, reaction time was reported to be 183 msec for men and 185 msec for women. Fast-forward to today, and the writers who were alarmed at how “dumb” we were becoming could point to any of several reports that clocked average reaction times at well over 220 msec – a 20% degradation!

So should we be alarmed? There are several possibilities that could lead to such a pronounced degradation in reaction time. After all, reaction time has been shown to be sensitive to many conditions, and it is a very good overall indicator of the health of the nervous system.

Sedentary lifestyles have been demonstrated to lead to poor reaction time performance, so perhaps this is just an indication of our shift from a predominantly agrarian society to urban or metropolitan lifestyles. This hypothesis parallels other investigations that have correlated worse reaction time scores (and/or decreased cognitive capacity) with less exercise, less time spent outdoors, recreational drugs and substance abuse, more stress, poor diet, and exposure to environmental toxins.

It is likely that these studies did not account for all the possible factors that could contribute to poor performance on the reaction time task. For example, in studies that report substance abuse, the healthy controls might simply be people that do not have substance abuse problems; none of the other factors listed above would be exclude subjects from serving as controls.

Before we start getting picky about how different studies are conducted in terms of identifying who is “healthy” and who is not, let’s do our own research on the topic.

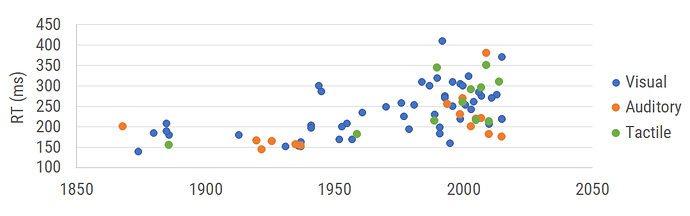

The graph below plots reaction time data in studies dating from the 1860s to present.

Note that from the 1860s to 1970s the average reaction times reported were all between 180 and 200 msec. However, after that, the data points become much more variable and tend to drift much higher – some into the 300-400 msec range, double what was reported in the 1880s! While there are ongoing epidemics in a number of neurological disorders over this time period (Alzheimer’s, autism spectrum disorders, chronic pain, etc.), the data points plotted represent the times reported for the healthy controls in each study.

What happened between 1970 and present day that could account for this drift?

Personal computers made it much easier for researchers to conduct reaction time studies. With the advent of afforable, portable computing, scientists no longer needed to depend on custom built timing devices or laboratory grade equipment for each study. Today, all that is needed to do a reaction time study is a computer or laptop: just flash an image on the screen and tell the subject which key to press. Simple, right?

Unfortunately, this simplicity overlooks the fact that every computer and associated operating system has inherent timing latencies – sometimes as much as 500 msec. Reaction times recorded using a personal computer will be much slower due to the latency, and since these latencies are hardware- and software-dependent, data collected on one computer system cannot necessarily be compared with data from another. We’ve reported on this latency before and you can read about it here.

What we had not done before is report on the historical data shown in the graph, which confirmed our suspicion that reaction times reported by others have gotten less and less accurate over the past 30-40 years (wow, that makes me feel old – I still remember setting up lab equipment 40 years ago that did not depend on consumer grade software and hardware). If the ability of current consumer-grade hardware and software (which is very good for what it is designed for) to work as lab equipment for collecting something like reaction time were actually getting better, then we suspect that the data points would be getting tighter and less variable historically rather than going in the opposite direction.

How does data collected with the Brain Gauge look? We are happy to say that the normative data we have collected with the Brain Gauge is very similar to what was reported in the 1880s (though the Brain Gauge is a bit more accurate, with 0.3 msec precision versus 10 msec). Sometimes, the old-fashioned ways work best.

Getting your reaction time to measure brain health is a bit like taking your temperature to measure body health: if there is anything acutely wrong, then the metric fluctuates from the norm. The methods developed to measure reaction time in the 1860s, though more labor-intensive and expensive than what can be done with any laptop today, were much more accurate.

To complete the temperature analogy, imagine taking your temp and getting a reading of either 90, 100 or 110. Not very useful, right? Well, that scale would be roughly equivalent to the accuracy level reported for most contemporary reaction time studies! Accuracy matters, and hat’s off to inventive scientists of the 1800s that got it right.